Tolkien et la révolution libertarienne

par Nicolas Bonnal

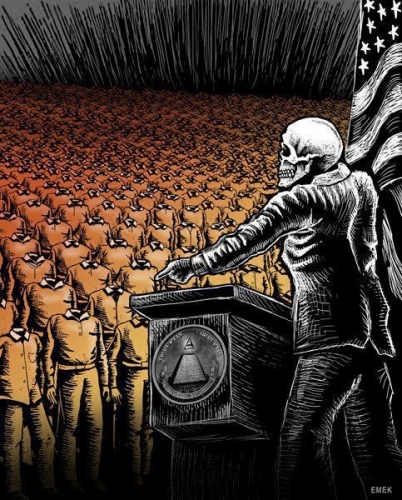

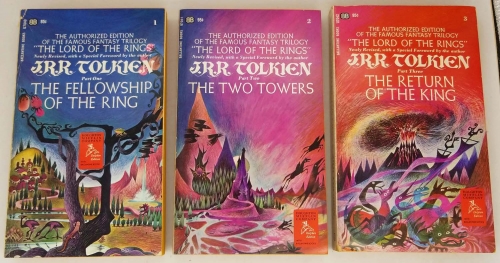

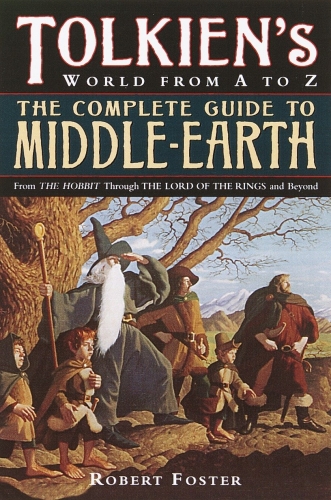

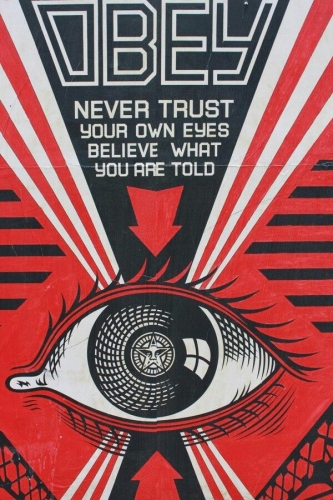

Relisons des extraits libertariens de notre dernier livre sur Tolkien, à l’heure où le Mordor américain devient fou – comme la Commission de Bruxelles, qui va imposer à son peuple d’orcs l’euro numérique, le contrôle social, le rationnement énergétique et le pass sanitaire avant d’en arriver à l’objectif ultime : le dépeuplement du continent (ou de ce qu’il en reste). Comme je l’ai montré dans mon livre Le salut par Tolkien (ou Le dernier Gardien sur Amazon), le bon chrétien Tolkien a été comme Chesterton un écrivain anti-Etat qui a vu la menace arriver non pas en Russie ou en Allemagne (ce serait trop facile) mais dans les mêmes pays anglo-saxons (cf. nos textes sur Hayek et Jouvenel). La dernière opération US aura montré que l’Ennemi triomphe parce qu’il est prêt à faire ce que les autres n’osent pas faire (Usual suspects repris par C. Johnston)

Chapitre sept in extenso (quatre mille mots) :

J'ai toujours eu un faible – Tolkien aussi d'ailleurs – pour le Nettoyage de la Comté, avant-dernier chapitre du Seigneur des Anneaux. Allusion au socialisme, à l'après-guerre, au monde moderne nihiliste et destructeur ? Volonté prosaïque de désigner un ennemi bien précis avec des problèmes bien concrets ? On récite le vieux Gamegie (Gaffer Gamgee, comme dit Tolkien) :

« Le Vieux Gamegie ne paraissait pas avoir pris beaucoup d'âge, mais il était un peu plus sourd. «Bonsoir, Monsieur Sacquet ! dit-il. Je suis bien heureux vraiment de vous voir revenu sain et sauf. Mais j'ai un petit compte à régler avec vous en quelque sorte, sauf votre respect. Vous n’auriez jamais dû vendre Cul de Sac, je l'ai toujours dit. C'est de ça qu'est parti tout le mal. Et pendant que vous alliez vagabonder dans les pays étrangers, à chasser les Hommes Noirs dans les montagnes, à ce que dit mon Sam et pourquoi, il ne me l'a pas trop expliqué ils sont venus défoncer le Chemin des Trous du Talus et ruiner mes patates (1)! »

Guerre concrète donc avec des objectifs concrets. C'est que de retour de leurs aventures hauturières et spirituelles, les Hobbits redécouvrent leur pays occupé et pillé par une horde de prévaricateurs, de pillards et de « réquisiteurs ». Ils les mettent dehors, sous la haute conduite de Sam et surtout de Merry et de Pippin, les deux Hobbits les plus aguerris par leurs campagnes, les plus transformés aussi par le « breuvage d'immortalité » fourni par Sylvebarbe. Le terme employé par Tolkien pour ce nettoyage est bien celui de « nettoyage à grandes eaux », scouring en anglais. Il s'agit d'une épuration physique d'un territoire violé par la modernité bruyante et travailleuse décrite par Tocqueville en Amérique du Nord (les Hobbits faisant ici office d'indiens). On peut bien sûr voir ici une « allégorie », terme décourageant et déplaisant pour Tolkien (quoique...) : comment les hommes libres et encore courageux peuvent se débarrasser de l'Etat moderne et tentaculaire, du fascisme du nazisme, du communisme, du socialisme, et de tout ce qui s'ensuit. Sans oublier le capitalisme et les aberrations du technologisme dénoncés par d'autres que Tolkien à son époque : de Morris à Mumford en passant par Ellul - ou le très bon Léopold Kohr, inspirateur du film thématique Koyaanisqatsi. Mais on verra que le ras-le-bol vis-à-vis de la « civilisation » est ancien.

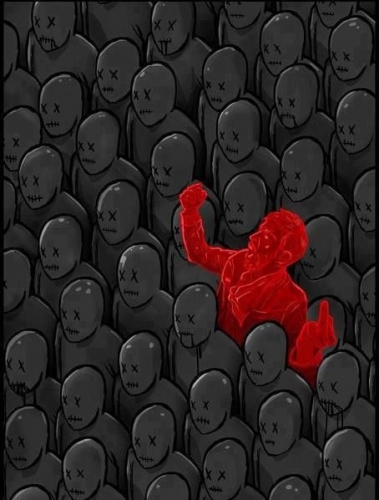

Comme on sait ce n'est pas si facile, et tout le monde a tendance à se soumettre et à s'arbrifier, comme dit Sylvebarbe.

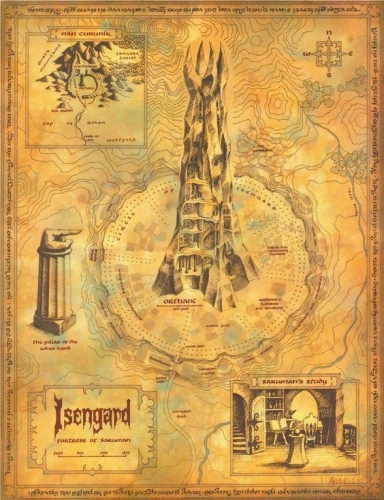

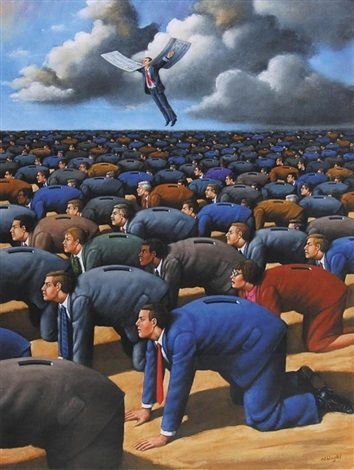

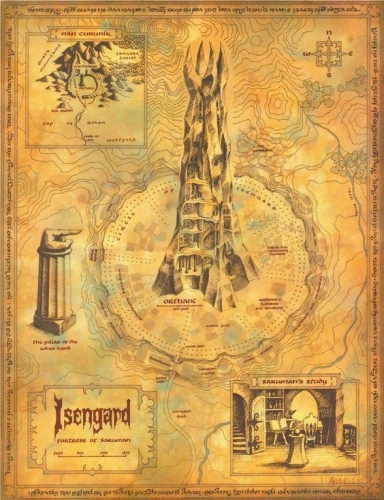

Le nettoyage de la comté est une grande fête de la subversion antigouvernementale ; c'est une révolte anarchiste, de type libertarien. Les grands historiens libertariens américains, sous la conduite de Murray Rothbard, de Ralph Raico, de John V. Denson, de Smedley Butler et de bien d'autres, ont montré que l'Etat américain a progressé en cruauté, en pression fiscale, en législation infernale, en aventurisme militaire depuis surtout Lincoln et la guerre de Cuba. Et que son interventionnisme devenu systématique a eu des conséquences catastrophiques, eschatologiques presque au niveau démographique (remplacement de la population américaine), juridique (abandon de la liberté), économique (assistanat généralisé et endettement), sociétal (fin de la famille, violence folle et prisons pleines) et même écologique (tout a été bousillé). La catastrophe s'est renforcée sous Woodrow Wilson, les deux Roosevelt, et ensuite, pour reprendre l'expression de Michael Levine, tout président s'est vu comme un social engineer, un ingénieur du social (sozial, disait Céline) charge de refaire le monde et son pays, c'est-à-dire de le démolir, de le polluer, de le souiller – sans oublier de le célébrer... Tout cela aboutit à la fronde menée par Donald Trump – avec toutes ses limites (2). Pour bien comprendre cette brillante et pessimiste école d'élite, on peut se référer à trois ouvrages collectifs fondamentaux, qui expliquent ce besoin démiurgique et satanique des élites occidentales modernes de refaire et de détruire le monde (3). C'est que Tolkien appelle l'esprit d'Isengard, en référence à Saroumane dans ses lettres.

Les libertariens américains aiment bien citer La Boétie et son impeccable Discours de la servitude volontaire (consultable partout) écrit lorsque ce jeune et bel esprit insatisfait de son temps avait seize ans à peine. Mais c'est plutôt Montaigne que j'aimerais citer, ce Montaigne si scolaire dont le bons sens et le scepticisme sont parfois un peu lassants, mais qui ici est tout bonnement impeccable : il s'agit du passage sur les cannibales, ces drôles d'oiseaux qui comme les Hobbits n'ont besoin de rien ou presque, proches en cela de notre état originel.

Les libertariens américains aiment bien citer La Boétie et son impeccable Discours de la servitude volontaire (consultable partout) écrit lorsque ce jeune et bel esprit insatisfait de son temps avait seize ans à peine. Mais c'est plutôt Montaigne que j'aimerais citer, ce Montaigne si scolaire dont le bons sens et le scepticisme sont parfois un peu lassants, mais qui ici est tout bonnement impeccable : il s'agit du passage sur les cannibales, ces drôles d'oiseaux qui comme les Hobbits n'ont besoin de rien ou presque, proches en cela de notre état originel.

Montaigne évoque Platon et son Atlantide (tiens, tiens...) dans le même texte :

« C’est un peuple, dirais-je à Platon, qui ne connaît aucune sorte de commerce ; qui n’a aucune connaissance des lettres ni aucune science des nombres ; qui ne connaît même pas le terme de magistrat, et qui ignore la hiérarchie ; qui ne fait pas usage de serviteurs, et ne connaît ni la richesse, ni la pauvreté ; qui ignore les contrats, les successions, les partages ; qui n’a d’autre occupation que l’oisiveté, nul respect pour la parenté autre qu’immédiate ; qui ne porte pas de vêtements, n’a pas d’agriculture, ne connaît pas le métal, pas plus que l’usage du vin ou du blé. Les mots eux-mêmes de mensonge, trahison, dissimulation, avarice, envie, médisance, pardon y sont inconnus. Platon trouverait-il la République qu’il a imaginée si éloignée de cette perfection (4) ? »

Et voici justement comment un Tolkien très inspiré présente sa comté, dans sa fameuse et si politique (ou apolitique !) introduction aux monde des Hobbits. Ce texte allait bien sûr inspirer certains hippies et tous les anti-système des années soixante, il allait le faire pour rien montrant finalement que le pessimisme de Tolkien n'était – n'est – pas si infondé que cela.

« La Comté n'avait guère à cette époque de «gouvernement. Les familles géraient pour la plus grande part leurs propres affaires. Faire pousser la nourriture et la consommer occupaient la majeure de leur temps. Pour le reste, ils étaient à l'ordinaire généreux et peu avides, et comme ils se contentaient de peu, les domaines, les fermes, les ateliers et les petits métiers avaient tendance à demeurer les mêmes durant des générations (5). »

On retrouve ici finalement une culture ancienne, assez païenne, fidèle au monde rustique et paysan célébré par les Anciens, notamment de Grèce ou de Rome ; et l'on est loin de Beowulf. Mais Tolkien est un tissu des rêves de l'histoire. Se contenter de peu (méden agan de Solon), la citoyenneté autonome (celui qui se donne à lui-même ses lois) qu'on retrouve aussi dans le romantisme allemand, la sociabilité et la libre transmission de l'héritage, sans que l'Etat vienne tout confisquer ou presque, la sécurité assurée par des milices, tout cela se retrouve dans la culture libertarienne.

Comme on sait un certain Lothon va vouloir développer le capitalisme dans la comté. Et cet enchaînement va amener la catastrophe : même idée pour les silmarils et le serment de Feanor qui amènent la chute du monde des elfes dans le Silmarillion.

Lorsque les Hobbits rentrent donc, on leur présente ainsi le tableau :

« On fait pousser beaucoup de nourriture, mais on ne sait pas au juste où ça passe. Ce sont tous ces "ramasseurs" et "répartiteurs", je pense, qui font des tournées pour compter, mesurer et emporter à l'emmagasinage. Ils font plus de ramassage que de répartition, et on ne revoit plus jamais la plus grande part des provisions (6)»

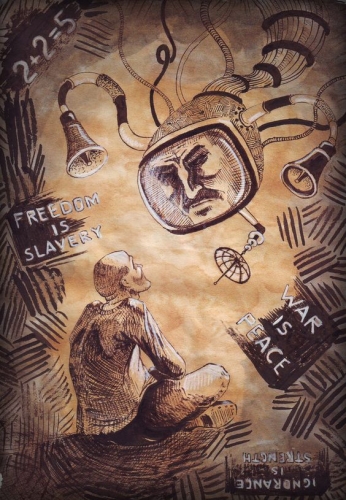

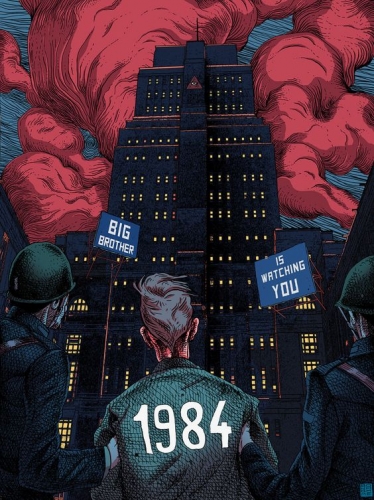

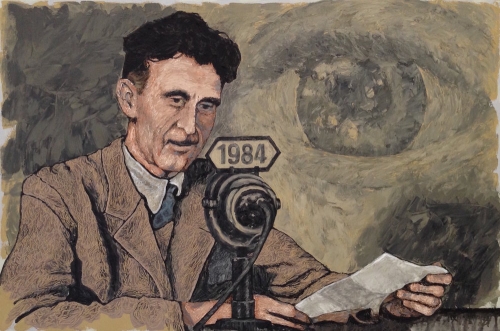

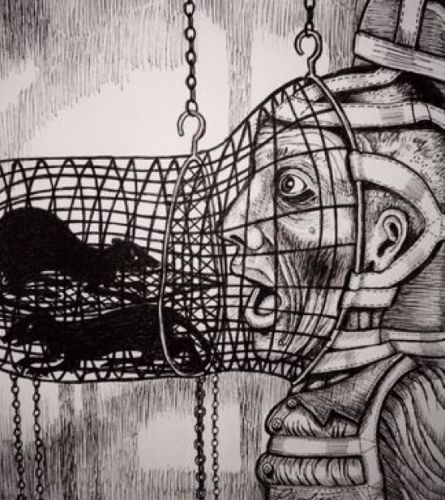

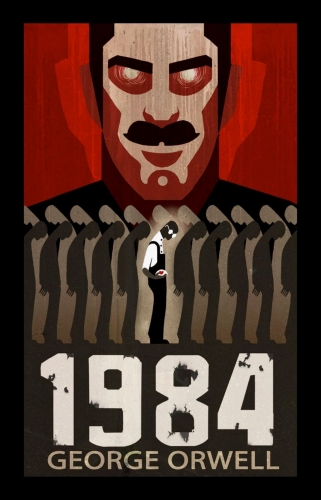

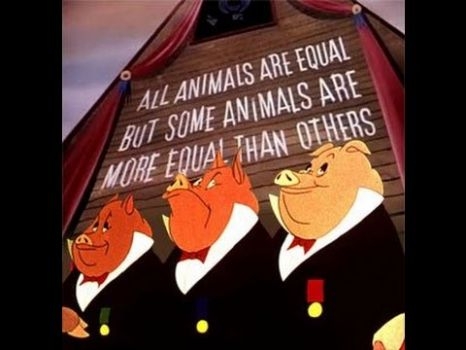

On pense bien sûr à l'Holodomor en Ukraine, où les équipes de tueurs venaient organiser une famine au nom du socialisme, du peuple et du reste. L'Angleterre de l'après-guerre, socialiste, travailliste et grise, ne sera pas en reste, qui imposera des rationnements dignes de temps de guerre – 80 gr. de beurre hebdomadaire, et dire que Hitler leur proposa dix fois la paix ! - et des taxations à plus de 90% sur les revenus. Ce n'est pas pour rien qu'Orwell publie à cette époque 1984.

La description de la nouvelle comté transformée en commune populaire par Sharcoux et son gang n'est pas triste non plus :

« C'était un endroit nu et laid, avec une toute petite grille qui ne permettait guère un bon feu. Dans les chambres du dessus, il y avait des petites rangées de lits durs, et sur tous les murs figuraient un écriteau et une liste de Règles. Pippin les arracha. Il n'y avait pas de bière, et seulement très peu de nourriture, mais avec ce que les voyageurs apportèrent et partagèrent, tous firent un repas convenable, et Pippin enfreignit la Règle N° 4 en mettant dans le feu la plus grande part de la ration de bois du lendemain. »

On se moque mais en sommes-nous si loin ? On veut interdire le feu de cheminée à Paris ; on est entouré d'interdictions, de panneaux indicateurs et de caméras de surveillance ; on ne cesse de mal ou moins (les régimes ou l'obésité) manger ; on est cernés aussi par des endroits nus et laids. Tout cela, nous nous y sommes habitués, parce que « nous nous habituons à tout » (Dostoïevski), en fait parce que nous devenons des esclaves. On travaille dans tous les pays du monde développé jusqu'au mois de juillet ou de septembre pour l'Etat redistributeur (sic). L'universitaire et penseur libertarien Smedley Butler (ci-dessous) a montré en fait comment ses étudiants écolos, végétariens, censeurs, anti-fumeurs sont plus proches d'Hitler que des pères fondateurs américains .

Butler écrit dans son anglais limpide et universitaire :

« He is an advocate of government gun-control measures. An ardent opponent of tobacco... This man is a champion of environmental and conservationist programs, and believes in the importance of sending troops into foreign countries in order to maintain order therein (7) .»

Tolkien ajoute sur le thème de la laideur, une laideur liée à novembre, et qui ne doit rien à Halloween (on le précise pour ceux qui croient...) :

« Le pays avait un aspect assez triste et désolé, mais c'était après tout le 1er Novembre et la queue de l'automne. Il semblait toutefois y avoir une quantité inhabituelle de feux, et de la fumée s'élevait en maints points alentour. Un grand nuage de cette fumée montait au loin dans la direction du Bout des Bois (8). »

Tolkien n'oublie pas la fumée des célèbres Dark satanic mills jadis dénoncées par William Blake, et qui ont aussi une signification spirituelle.

Et Frodon rappelle aux miliciens humiliés par ses compagnons hilares mais menaçants la nécessité de la liberté de mouvement – sans les contrôles scandaleux de nos aéroports :

« A la déconfiture des Shiriffes, Frodon et ses compagnons rirent à gorge déployée. «Ne soyez donc pas absurde ! dit Frodon. Je vais où il me plaît et quand je le veux. Il se trouve que je me rends à Cul de Sac pour affaires, mais si vous tenez à y aller aussi, c'est la vôtre (9).»

Puis le sabotage du paysage apparaît dans toute son erreur. La sensibilité à la laideur est venue avec William Morris ou les préraphaélites mais des esprits plus vifs comme Blake ou Chateaubriand l'avaient saisie avant.

« Ils éprouvèrent le premier choc vraiment pénible. C'était le propre pays de Frodon et de Sam, et ils découvrirent alors qu'ils y étaient plus attachés qu'à aucun autre lieu du monde. Un bon nombre de maisons qu'ils avaient connues manquaient. Certaines semblaient avoir été incendiées. L'agréable rangée d'anciens trous de Hobbits dans le talus du côté nord de l'Étang était abandonnée, et les petits jardins, qui descendaient autrefois, multicolores, jusqu'au bord de l'eau, étaient envahis de mauvaises herbes. Pis encore, il y avait une ligne entière des vilaines maisons neuves tout le long de la Promenade de l'Étang, où la Route de Hobbitebourg suivait la rive. Il y avait autrefois une avenue d'arbres. Ils avaient tous disparu. Et, regardant avec consternation le long de la route en direction de Cul de Sac, ils virent au loin une haute cheminée de brique. Elle déversait une fumée noire dans l'air du soir (10). »

Les voyous prétendent comme les prophètes, les nazis ou les communistes « réveiller » les endormis (il faut les réveiller en fait, mais pour les bonnes raisons – voir infra) :

«Ce pays a besoin d'être réveillé et remis en ordre, dit le bandit, et Sharcoux va le faire, et il sera dur, si vous l'y poussez. Vous avez besoin d'un plus grand Patron. Et vous allez l'avoir avant la fin de l'année, s'il y a encore des difficultés. Et vous apprendrez une ou deux choses, sale petit rat (11). »

Frodon lui se présente comme un restaurateur de la tradition, s'appuyant sur ce qui vient d'être accompli – et qui n'est pas connu dans la comté dominée:

« Votre temps est fini, comme celui de tous les autres bandits. La Tour Sombre est tombée, et il y a un Roi en Gondor. L'Isengard a été détruit, et votre beau maître n'est plus qu'un mendiant dans le désert. J'ai passé près de lui sur la route. Les messagers du Roi vont remonter le Chemin Vert à présent, et non plus les brutes de l'Isengard... Je suis un messager du Roi, dit-il. Vous parlez à l'ami du Roi et une des personnes les plus renommées des pays de l'Ouest. Vous êtes un coquin et un imbécile (12). »

Du même coup on rappelle l'origine du mal :

«Tout a commencé avec La Pustule, comme on l'appelle, dit le Père Chaumine, et ça a commencé aussitôt après votre départ, Monsieur Frodon. Il avait de drôles d'idées, ce La Pustule. II semble qu'il voulait tout posséder en personne, et puis faire marcher les autres. Il se révéla bientôt qu'il en avait déjà plus qu'il n'était bon pour lui, et il était tout le temps à en raccrocher davantage, et c'était un mystère d'où il tirait l'argent: des moulins et des malteries, des auberges, des fermes et des plantations d'herbe. Il avait déjà acheté le moulin de Rouquin avant de venir à Cul de Sac, apparemment. »

Oui, c'est un mystère en effet d'où l'on tire l'argent. Une banque centrale invisible peut-être ?

Le réveil arrive, mais il va se faire contre les brigands et leur chef naturellement. Tolkien évoque le cor, si important pour Boromir, et qui symbolise, comme dans notre Chanson de Roland, le réveil de notre tradition supérieure.

« Puis il entendit Merry changer de note, et l'appel de cor du Pays de Bouc s'éleva, secouant l'air... Sam entendit derrière lui un tumulte de voix, un grand remue-ménage et des claquements de portes. Devant lui, des lumières jaillirent dans le crépuscule, des chiens aboyèrent, des pas accoururent. Avant qu'il n'eût atteint le bout du chemin, il vit se précipiter vers lui le Père Chaumine avec trois de ses gars, Tom le Jeune, Jolly et Nick. Ils portaient des haches et barraient la route (13). »

On se réveille, on s'arme, on allume des feux, comme pour une fête de la Saint-Jean. C'est la révolution.

« A son retour, Sam trouva tout le village en ébullition. Déjà, en dehors de nombreux garçons plus jeunes, une centaine ou davantage de robustes Hobbits étaient rassemblés, munis de haches, de lourds marteaux, de long couteaux et de solides gourdins, et quelques-uns portaient des arcs de chasse. D'autres encore venaient de fermes écartées.

Des gens du village avaient allumé un grand feu, juste pour animer le tableau, mais aussi parce que c'était une des choses interdites par le Chef. II flambait joyeusement dans la nuit tombante (14). »

Tels des chouans chanceux, tels les héros de Chesterton dans le Napoléon de Notting Hill, les Hobbits vont se pouvoir résister et se battre :

« Mais les Touque arrivèrent avant. Ils firent bientôt leur entrée, au nombre d'une centaine, venant de Bourg de Touque et des Collines Vertes avec Pippin à leur tête. Merry eut alors suffisamment de robuste Hobbiterie pour recevoir les bandits. Des éclaireurs rendirent compte que ceux-ci se tenaient en troupe compacte. Ils savaient que le pays s'était soulevé contre eux, et ils avaient clairement l’intention de réprimer impitoyablement la rébellion, en son centre de Lézeau. Mais, si menaçants qu'ils pussent être, ils semblaient n'avoir parmi eux aucun chef qui s'entendît à la guerre. Ils avançaient sans aucune précaution. Merry établit vite ses plans (15). »

La révolution libertarienne à la sauce Guillaume Tell porte ses fruits. La restauration va se passer merveilleusement, et donc métamorphoser la contrée (Tolstoï aussi décrit la belle résurrection moscovite après la retraite des Français) :

« Cependant, les travaux de restauration allèrent bon train, et Sam fut très occupé. Les Hobbits peuvent travailler comme des abeilles quand l'humeur et la nécessité les prennent. Il y eut alors des milliers de mains volontaires de tous âges, de petites mais agiles des garçons et filles Hobbits à celles usées et calleuses des anciens et des vieilles. Avant la fin de Décembre, il ne restait plus brique sur brique des nouvelles Maisons des Shiriffes ou de quoi que ce fût de ce qu'avaient édifié les «Hommes de Sharcoux», mais les matériaux servirent à réparer maints vieux trous et à les rendre plus confortables et plus secs (16). »

Et là, miraculeusement, d'une manière digne de la quatrième églogue de Virgile, une résurrection de la terre et des naissnaces survient, un nouvel âge d'or :

« De tout point de vue, 1420 fut dans la Comté une année merveilleuse. Il n'y eut pas seulement un soleil magnifique et une pluie délicieuse aux moments opportuns et en proportion parfaite, mais quelque chose de plus, semblait-il: un air de richesse et de croissance, et un rayonnement de beauté surpassant celui des étés mortels qui vacillent et passent sur cette Terre du Milieu (17). »

Cette beauté terrestre va se retrouver dans le monde humain.

« Tous les enfants nés ou conçus en cette année, et il y en eut beaucoup, étaient robustes et beaux, et la plupart avaient une riche chevelure dorée, rare auparavant parmi les Hobbits. Il y eut une telle abondance de fruits que les jeunes Hobbits baignaient presque dans les fraises à la crème, et après, ils s'installaient sur les pelouses sous les pruniers et mangeaient jusqu'à élever des monceaux de noyaux semblables à de petites pyramides ou aux crânes entassés par un conquérant, après quoi, ils allaient plus loin. Et personne n'était malade, et tout le monde était heureux, sauf ceux à qui il revenait de tondre l'herbe (18). »

Et puisque nous évoquions Virgile :

« Muses de Sicile, élevons un peu nos chants. Les buissons ne plaisent pas à tous, non plus que les humbles bruyères. Si nous chantons les forêts, que les forêts soient dignes d'un consul. Il s'avance enfin, le dernier âge prédit par la Sibylle : je vois éclore un grand ordre de siècles renaissants. Déjà la vierge Astrée revient sur la terre, et avec elle le règne de Saturne ; déjà descend des cieux une nouvelle race de mortels. Souris, chaste Lucine, à cet enfant naissant ; avec lui d'abord cessera l'âge de fer, et à la face du monde entier s'élèvera l'âge d'or : déjà règne ton Apollon (19). »

Les conséquences ? La révolution libertarienne des Hobbits a une dimension lumineuse, propitiatoire. Dans son beau livre sur le moyen âge, Jacques Le Goff écrivait :

« Un autre courant tout aussi puissant a entraîné beaucoup d'entre eux vers un autre espoir, vers un autre désir : la réalisation sur terre du bonheur éternel, le retour à l'âge d'or, au paradis perdu. Ce courant, c'est celui du millénarisme, le rêve d'un millenium - d'une période de mille ans (20)... »

Concluons en nous référant aux rares idées politiques exprimées par Tolkien. Rares parce qu'inutiles : Tolkien est contre tout Big Government à la moderne. Carpenter le dit right-wing, d'extrême-droite parce qu'il est monarchiste et catholique. Et si c'était cela être de gauche par les temps qui courent ?

Tolkien ne se disait évidemment pas libertarien ; mais il n'a pas hésité à se déclarer... anarchiste !!! Ou monarchiste non constitutionnel... mais on se doute que la monarchie des Windsor n'est pas la tasse de thé de Tolkien... Il lui faudrait le grand Alfred ou quelque monarque saxon... Il écrit donc à notre cher Christopher qu'il hait l'Etat :

« My political opinions lean more and more to Anarchy (philosophically understood, meaning abolition of control not whiskered men with bombs) – or to 'unconstitutional' Monarchy. I would arrest anybody who uses the word State (21)...»

Toujours au même Christopher, il rappelle son peu de goût pour la démocratie à la grecque ou à la moderne, conçue comme une ochlocratie, un gouvernement de la masse. Il en profite pour tacler l'odieux et désastreux Anthony Eden et rappeler le dégoût inspiré par ce système aux grands penseurs de l'Antiquité :

« Mr Eden in the house the other day expressed pain at the occurrences in Greece 'the home of democracy'. Is he ignorant, or insincere? d?µ???at?a was not in Greek a word of approval but was nearly equivalent to 'mob-rule'; and he neglected to note that Greek Philosophers – and far more is Greece the home of philosophy – did not approve of it. And the great Greek states, esp. Athens at the time of its high an and power, were rather Dictatorships, if they were not military monarchies like Sparta (22)! »

Dans un très beau brouillon, Tolkien répond s'exprime même sur le nettoyage de la comté ! L'anglais est encore ici très simple :

« There is no special reference to England in the 'Shire' – except of course that as an Englishman brought up in an 'almost rural' village of Warwickshire on the edge of the prosperous bourgeoisie of Birmingham. But there is no post-war reference. I am not a 'socialist' in any sense — being averse to 'planning' (as must be plain) most of all because the 'planners', when they acquire power, become so bad (23)... »

Et sur cet esprit d'Isengard qui détruira tout, Oxford y compris :

« Though the spirit of 'Isengard', if not of Mordor, is of course always cropping up. The present design of destroying Oxford in order to accommodate motor-cars is a case. But our chief adversary is a member of a 'Tory' Government. But you could apply it anywhere in these days (24). »

Et on comprend que peu importe le parti politique ici...

Notes du chapitre VII:

(1) Le retour du roi, Chapitre le nettoyage de la comté

(2) Nicolas Bonnal, Donald Trump candidat du chaos, Dualpha, 2016

(3) Perpetual war for perpetual peace, 1953 ; The costs of war, 1999 ; reassessing the presidency, 2001. Tout est téléchargeable gratuitement sur le beau site Mises.org

(4) Montaigne, Essais, I, chapitre 30, § 16

(5) La communauté de l'anneau, Chapitre 1, Des Hobbits

(6) Le nettoyage de la comté. III, livre VI, chapitre 8

(7) Smedley Butler, The wizards of Ozymandia, 2002, § 30

(8) Le nettoyage de la comté. (III, livre VI, chapitre 8)

(9) Le nettoyage de la comté. (III, livre VI, chapitre 8)

(10) ibid.

(11) ibid.

(12) ibid.

(13) ibid.

(14) ibid.

(15) ibid.

(16) ibid.

(17) ibid.

(18) ibid.

(19) Virgiles, Bucoliques, IV, premiers vers.

(20) Le Goff, la civilisation de l'occident médiéval, Arthaud, p. 163

(21) Letters of Tolkien, From a letter to Christopher Tolkien 29 November 1943

(22) Letters of Tolkien, To Christopher Tolkien, 28 December 1944 (FS 71)

(23) To Michael Straight [drafts], february 1956

(24) ibid.

On connaît tous les Hérétiques de Chesterton, recueil où Chesterton exécute, au début du siècle dernier, les tenanciers anglo-saxons des hérésies modernes (à commencer par l’impérialiste Kipling) : Chesterton voit venir les végétariens avec leurs gros sabots, les « remplacistes » proches des impérialistes (Le Retour de Don Quichotte), les féministes et l’interdiction de manger de l’herbe. Dans l’Auberge volante il prévoit aussi une interdiction des ventes d’alcool sur fond de credo hostile – d’où le vol de l’auberge. Chesterton avait aussi vu le danger du salariat de masse ; dans le Club des métiers bizarres (Club of Queer trades) ce libertarien chrétien défend la possibilité d’inventer un métier qui n’existe pas – et qui rapporte. Cette intuition géniale a servi d’inspiration au grand film de David Fincher, The Game. C’est l’Agence de l’aventure et de l’inattendu.

On connaît tous les Hérétiques de Chesterton, recueil où Chesterton exécute, au début du siècle dernier, les tenanciers anglo-saxons des hérésies modernes (à commencer par l’impérialiste Kipling) : Chesterton voit venir les végétariens avec leurs gros sabots, les « remplacistes » proches des impérialistes (Le Retour de Don Quichotte), les féministes et l’interdiction de manger de l’herbe. Dans l’Auberge volante il prévoit aussi une interdiction des ventes d’alcool sur fond de credo hostile – d’où le vol de l’auberge. Chesterton avait aussi vu le danger du salariat de masse ; dans le Club des métiers bizarres (Club of Queer trades) ce libertarien chrétien défend la possibilité d’inventer un métier qui n’existe pas – et qui rapporte. Cette intuition géniale a servi d’inspiration au grand film de David Fincher, The Game. C’est l’Agence de l’aventure et de l’inattendu.

J’oubliais : dans What I saw in America, Chesterton dénonce son arrivée en Amérique après la Guerre. On contrôle tout et on ausculte tout pour savoir si le voyageur ou l’émigrant européen, devenu soudain un pestiféré, ne s’est pas fait inaugurer le virus du communisme ou de l’anarchisme. Le tout évidemment sur fond de chasse aux buveurs de bière. La Prohibition est puritaine et pas musulmane. Avec des défenseurs de la Liberté comme les Yankees qui avait rasé le Sud après la Guerre de Sécession, et qui aujourd’hui interdisent sur ordre des actionnaires sexe, famille, patriotisme ou race, Chesterton savait qu’on aurait du souci à se faire. Et dans le même opus, il voit la terrible menace féministe américaine se pointer.

J’oubliais : dans What I saw in America, Chesterton dénonce son arrivée en Amérique après la Guerre. On contrôle tout et on ausculte tout pour savoir si le voyageur ou l’émigrant européen, devenu soudain un pestiféré, ne s’est pas fait inaugurer le virus du communisme ou de l’anarchisme. Le tout évidemment sur fond de chasse aux buveurs de bière. La Prohibition est puritaine et pas musulmane. Avec des défenseurs de la Liberté comme les Yankees qui avait rasé le Sud après la Guerre de Sécession, et qui aujourd’hui interdisent sur ordre des actionnaires sexe, famille, patriotisme ou race, Chesterton savait qu’on aurait du souci à se faire. Et dans le même opus, il voit la terrible menace féministe américaine se pointer.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Les libertariens américains aiment bien citer La Boétie et son impeccable Discours de la servitude volontaire (consultable partout) écrit lorsque ce jeune et bel esprit insatisfait de son temps avait seize ans à peine. Mais c'est plutôt Montaigne que j'aimerais citer, ce Montaigne si scolaire dont le bons sens et le scepticisme sont parfois un peu lassants, mais qui ici est tout bonnement impeccable : il s'agit du passage sur les cannibales, ces drôles d'oiseaux qui comme les Hobbits n'ont besoin de rien ou presque, proches en cela de notre état originel.

Les libertariens américains aiment bien citer La Boétie et son impeccable Discours de la servitude volontaire (consultable partout) écrit lorsque ce jeune et bel esprit insatisfait de son temps avait seize ans à peine. Mais c'est plutôt Montaigne que j'aimerais citer, ce Montaigne si scolaire dont le bons sens et le scepticisme sont parfois un peu lassants, mais qui ici est tout bonnement impeccable : il s'agit du passage sur les cannibales, ces drôles d'oiseaux qui comme les Hobbits n'ont besoin de rien ou presque, proches en cela de notre état originel.

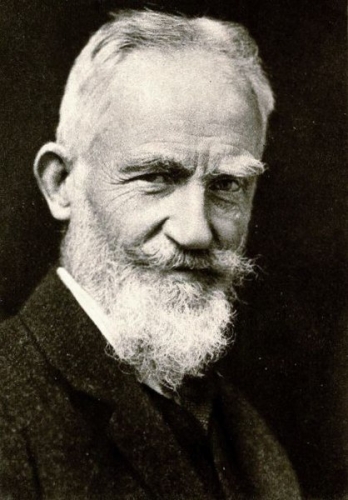

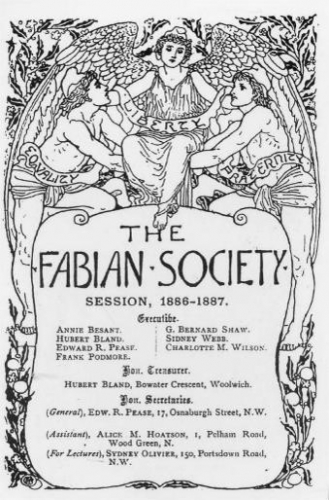

Cette idée est complétée par la préface et le manuel du révolutionnaire. L'auteur y explique que le socialisme a toujours échoué parce que, jusqu'à présent, l'inégalité des biens n'a pas empêché l'humanité de survivre. Mais cela change avec la mondialisation. Un monde de plus en plus complexe nécessite un nouvel homme, meilleur que tous les précédents, qui serait capable de le gérer. Le surhomme devient une nécessité. Mais comment en fournir un ? George Bernard Shaw voit la solution dans l'eugénisme d'État. Si l'humanité y accède, il ne s'agira, selon Shaw, que d'un changement quantitatif, puisque l'État a toujours choisi des partenaires pour ses dirigeants : les héritiers du trône. Cependant, puisque les pays modernes ne sont plus gouvernés par des monarques mais par le peuple, il est nécessaire de rechercher rationnellement des contreparties à ce nouveau souverain, les masses démocratiques. Les oligarchies, juge l'écrivain, sont tombées parce qu'elles n'ont pas trouvé un seul surhomme à leur tête. La démocratie peut donc d'autant moins fonctionner que nous n'élevons pas un électorat de surhommes (2).

Cette idée est complétée par la préface et le manuel du révolutionnaire. L'auteur y explique que le socialisme a toujours échoué parce que, jusqu'à présent, l'inégalité des biens n'a pas empêché l'humanité de survivre. Mais cela change avec la mondialisation. Un monde de plus en plus complexe nécessite un nouvel homme, meilleur que tous les précédents, qui serait capable de le gérer. Le surhomme devient une nécessité. Mais comment en fournir un ? George Bernard Shaw voit la solution dans l'eugénisme d'État. Si l'humanité y accède, il ne s'agira, selon Shaw, que d'un changement quantitatif, puisque l'État a toujours choisi des partenaires pour ses dirigeants : les héritiers du trône. Cependant, puisque les pays modernes ne sont plus gouvernés par des monarques mais par le peuple, il est nécessaire de rechercher rationnellement des contreparties à ce nouveau souverain, les masses démocratiques. Les oligarchies, juge l'écrivain, sont tombées parce qu'elles n'ont pas trouvé un seul surhomme à leur tête. La démocratie peut donc d'autant moins fonctionner que nous n'élevons pas un électorat de surhommes (2).

L'auteur affirme qu'il n'a trouvé qu'une inspiration marginale pour son surhomme chez Nietzsche. Teilhard de Chardin, quant à lui, ne revendique pas l'influence de Shaw, bien que son surhomme ait plusieurs points de contact avec celui de Shaw. Comme George Bernard Shaw, le paléontologue jésuite n'appelle pas à un "individu supérieur" mais à l'ensemble du surhomme. Dans l'œuvre de Teilhard aussi, l'évolution elle-même prend le contrôle, ayant appris à se connaître à travers le cerveau humain. Il appelle lui aussi à un "eugénisme" qui, toutefois, ne se souciera pas de la race. Et les deux philosophes voient le moteur de l'évolution dans la clarification de la conscience. Pour le penseur chrétien, cette clarification consiste en une convergence toujours plus étroite des esprits individuels ; pour Shaw, en une meilleure connaissance de soi et de la réalité, à laquelle doit conduire la concurrence sans frein des opinions. Mais parallèlement, GBS cherche aussi à dépasser le "particularisme" par le "service de la vie", une force universelle commune à tous les hommes et à tous les animaux (3). Pourtant, le surhomme de Shaw a un objectif différent de celui de Teilhard - il ne cherche pas à fusionner avec Dieu, bien qu'il ne soit pas non plus dépourvu de certains éléments religieux.

L'auteur affirme qu'il n'a trouvé qu'une inspiration marginale pour son surhomme chez Nietzsche. Teilhard de Chardin, quant à lui, ne revendique pas l'influence de Shaw, bien que son surhomme ait plusieurs points de contact avec celui de Shaw. Comme George Bernard Shaw, le paléontologue jésuite n'appelle pas à un "individu supérieur" mais à l'ensemble du surhomme. Dans l'œuvre de Teilhard aussi, l'évolution elle-même prend le contrôle, ayant appris à se connaître à travers le cerveau humain. Il appelle lui aussi à un "eugénisme" qui, toutefois, ne se souciera pas de la race. Et les deux philosophes voient le moteur de l'évolution dans la clarification de la conscience. Pour le penseur chrétien, cette clarification consiste en une convergence toujours plus étroite des esprits individuels ; pour Shaw, en une meilleure connaissance de soi et de la réalité, à laquelle doit conduire la concurrence sans frein des opinions. Mais parallèlement, GBS cherche aussi à dépasser le "particularisme" par le "service de la vie", une force universelle commune à tous les hommes et à tous les animaux (3). Pourtant, le surhomme de Shaw a un objectif différent de celui de Teilhard - il ne cherche pas à fusionner avec Dieu, bien qu'il ne soit pas non plus dépourvu de certains éléments religieux.

Robert GRAVES, 1895-1985, est un poète et romancier britannique, spécialiste des mythes et de l'Antiquité, il a connu le succès avec sa trilogie romanesque sur l'Empire romain, "Moi, Claude" et avec son récit " Les Mythes Grecs".

Robert GRAVES, 1895-1985, est un poète et romancier britannique, spécialiste des mythes et de l'Antiquité, il a connu le succès avec sa trilogie romanesque sur l'Empire romain, "Moi, Claude" et avec son récit " Les Mythes Grecs".

C'est évidemment à la lumière de ces énormes traumatismes communs à toute une génération de jeunes hommes comme son ami et alter ego le poète et capitaine Siegfried SASSOON , qu'il faut comprendre comment, après la victoire alliée de 1918 et la fin de ses études à Oxford, ou il s'est lié d'amitié avec le colonel T.E LAWRENCE alors en pleine écriture des Sept Piliers et l'écrivain et poète TS ELIOT notamment, il est amené à partir pour l'Egypte et à réviser nombre de ses opinions sur l'Angleterre qu'il a connue avant la guerre. L'horreur de ses souvenirs avait suscité une telle amertume chez le jeune homme qu'il était encore que, incapable de vivre au pays, il se sépara de sa première femme ( ils avaient eu quatre enfants) et s'installa à Majorque. Dans la beauté d'un paysage à mille lieues de la boue, des rats, du froid, de la putréfaction des cadavres, du sifflement des balles et des hurlements déchirants de blessés qui mettaient souvent plusieurs jours à mourir dans le no man's land entre les tranchées adverses si proches les unes des autres, il acheva la rédaction de cette autobiographie.

C'est évidemment à la lumière de ces énormes traumatismes communs à toute une génération de jeunes hommes comme son ami et alter ego le poète et capitaine Siegfried SASSOON , qu'il faut comprendre comment, après la victoire alliée de 1918 et la fin de ses études à Oxford, ou il s'est lié d'amitié avec le colonel T.E LAWRENCE alors en pleine écriture des Sept Piliers et l'écrivain et poète TS ELIOT notamment, il est amené à partir pour l'Egypte et à réviser nombre de ses opinions sur l'Angleterre qu'il a connue avant la guerre. L'horreur de ses souvenirs avait suscité une telle amertume chez le jeune homme qu'il était encore que, incapable de vivre au pays, il se sépara de sa première femme ( ils avaient eu quatre enfants) et s'installa à Majorque. Dans la beauté d'un paysage à mille lieues de la boue, des rats, du froid, de la putréfaction des cadavres, du sifflement des balles et des hurlements déchirants de blessés qui mettaient souvent plusieurs jours à mourir dans le no man's land entre les tranchées adverses si proches les unes des autres, il acheva la rédaction de cette autobiographie.

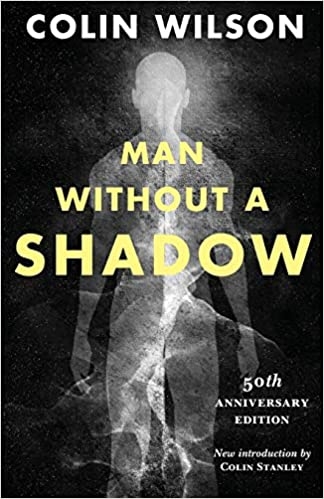

Le deuxième volume de la trilogie, récemment publié, L'homme sans ombre (Carbonio editore, 299 p., 16,50 euros) peut être lu et apprécié indépendamment du premier livre, étant un autre chapitre de la vie de l'écrivain Gérard Sorme, cette fois-ci centré sur le sexe : une sorte de "journal intime" comme le dit le sous-titre. Pour Sorme, le sexe est un élément d'inspiration pour ses histoires, afin d'élargir sa conscience, un peu comme à Londres dans les années 60 où l'on affirmait la consommation de drogues, et donc il s'engage à avoir une vie intense dans ce domaine et, dans un journal intime, il transcrit ses expériences, ses rencontres, les filles avec lesquelles il sort et ses pensées à leur sujet. Gertrude, Caroline, Madeleine, Charlotte, Mary, les femmes et les visages, les mots et les corps se succèdent jusqu'à ce qu'il rencontre et conquière Diana, une femme mariée à un musicien fou qui est un peu plus âgée qu'elle. Gérard tombe profondément amoureux.

Le deuxième volume de la trilogie, récemment publié, L'homme sans ombre (Carbonio editore, 299 p., 16,50 euros) peut être lu et apprécié indépendamment du premier livre, étant un autre chapitre de la vie de l'écrivain Gérard Sorme, cette fois-ci centré sur le sexe : une sorte de "journal intime" comme le dit le sous-titre. Pour Sorme, le sexe est un élément d'inspiration pour ses histoires, afin d'élargir sa conscience, un peu comme à Londres dans les années 60 où l'on affirmait la consommation de drogues, et donc il s'engage à avoir une vie intense dans ce domaine et, dans un journal intime, il transcrit ses expériences, ses rencontres, les filles avec lesquelles il sort et ses pensées à leur sujet. Gertrude, Caroline, Madeleine, Charlotte, Mary, les femmes et les visages, les mots et les corps se succèdent jusqu'à ce qu'il rencontre et conquière Diana, une femme mariée à un musicien fou qui est un peu plus âgée qu'elle. Gérard tombe profondément amoureux. Wilson dans Night Rites fait référence au crime et à la recherche de la définition mentale d'un jeu psychologique qui pourrait obséder le tueur en série. Au contraire, au centre du récit de L'Homme sans ombre, il n'y a pas vraiment que le sexe, comme les critiques et l'auteur lui-même voudraient nous le faire croire. Il y en a, bien sûr, mais avec une plus grande prépondérance de la magie. En fait, dans la première partie, Wilson déclare : "Je suis certain d'une chose : l'énergie sexuelle est aussi proche de la magie - du surnaturel - que les êtres humains en ont jamais fait l'expérience. Elle mérite une étude continue et attentive. Aucune étude n'est aussi profitable pour le philosophe. Dans l'énergie sexuelle, il peut observer le but de l'univers en action". Cette phrase, qui dans la réalité moderne et dans le Londres du Swinging des années 1960, était considérée comme l'exaltation des sens et de la luxure sexuelle comme la gratification du désir, renvoie en fait à un thème central de la magie : l'utilisation de la plus grande force existante - le sexe - pour accéder aux forces de l'Univers et plier les forces de la nature (mentionnée à plusieurs reprises par l'écrivain anglais) à sa volonté. Un enseignement qui est présent dans toutes les doctrines ésotériques de n'importe quelle partie du monde (Cf. Evola, Metafisica del sesso, Ed. Mediterranee ; Weininger, Sesso e carattere, Ed. Mediterranee, etc.). Mais le monde moderne n'interprète le sexe que dans une dimension consumériste et comme une source de plaisir physique, et c'est tout.

Wilson dans Night Rites fait référence au crime et à la recherche de la définition mentale d'un jeu psychologique qui pourrait obséder le tueur en série. Au contraire, au centre du récit de L'Homme sans ombre, il n'y a pas vraiment que le sexe, comme les critiques et l'auteur lui-même voudraient nous le faire croire. Il y en a, bien sûr, mais avec une plus grande prépondérance de la magie. En fait, dans la première partie, Wilson déclare : "Je suis certain d'une chose : l'énergie sexuelle est aussi proche de la magie - du surnaturel - que les êtres humains en ont jamais fait l'expérience. Elle mérite une étude continue et attentive. Aucune étude n'est aussi profitable pour le philosophe. Dans l'énergie sexuelle, il peut observer le but de l'univers en action". Cette phrase, qui dans la réalité moderne et dans le Londres du Swinging des années 1960, était considérée comme l'exaltation des sens et de la luxure sexuelle comme la gratification du désir, renvoie en fait à un thème central de la magie : l'utilisation de la plus grande force existante - le sexe - pour accéder aux forces de l'Univers et plier les forces de la nature (mentionnée à plusieurs reprises par l'écrivain anglais) à sa volonté. Un enseignement qui est présent dans toutes les doctrines ésotériques de n'importe quelle partie du monde (Cf. Evola, Metafisica del sesso, Ed. Mediterranee ; Weininger, Sesso e carattere, Ed. Mediterranee, etc.). Mais le monde moderne n'interprète le sexe que dans une dimension consumériste et comme une source de plaisir physique, et c'est tout. Un jeune homme en colère

Un jeune homme en colère

In the

In the

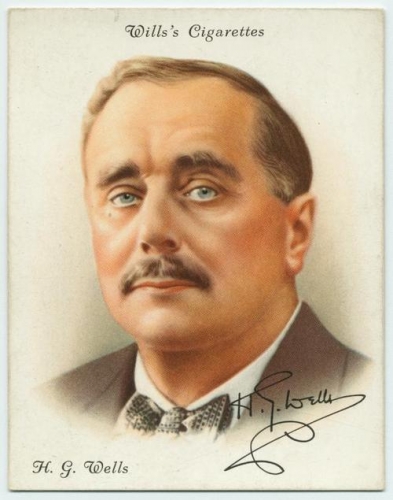

Wells was himself the son of a lowly gardener, but, like Huxley, exhibited a strong misanthropic wit, passion and creativity lacking in the high nobility, and he was thus raised from the lower ranks of society into the order of oligarchical management by the 1890s. During this moment of vast potential- and – it cannot be restated enough- the oligarchical order that had grown overconfident during the 200+ years of hegemony were petrified to see the nations of the earth rapidly

Wells was himself the son of a lowly gardener, but, like Huxley, exhibited a strong misanthropic wit, passion and creativity lacking in the high nobility, and he was thus raised from the lower ranks of society into the order of oligarchical management by the 1890s. During this moment of vast potential- and – it cannot be restated enough- the oligarchical order that had grown overconfident during the 200+ years of hegemony were petrified to see the nations of the earth rapidly  H.G Wells, Russell and other early social engineers of this new priesthood organized themselves in several interconnected think tanks known as 1) the

H.G Wells, Russell and other early social engineers of this new priesthood organized themselves in several interconnected think tanks known as 1) the

By the time World War II began, Wells’ ideas had evolved new insidious components that later gave rise to such mechanisms as Wikipedia and Twitter in the form of

By the time World War II began, Wells’ ideas had evolved new insidious components that later gave rise to such mechanisms as Wikipedia and Twitter in the form of

Although the bodies of Wells, Russell and Huxley have long since rotted away, their rotten ideas continue to animate their disciples like Sir Henry Kissinger, George Soros, Klaus Schwab, Bill Gates, Lord Malloch-Brown (whose disturbing

Although the bodies of Wells, Russell and Huxley have long since rotted away, their rotten ideas continue to animate their disciples like Sir Henry Kissinger, George Soros, Klaus Schwab, Bill Gates, Lord Malloch-Brown (whose disturbing

But amid all their countless fiascoes and failures in every other field (including the highest per capita death rate from COVID-19 in Europe, and one of the highest in the world) the British remain world leaders at managing global Fake News. As long as the tone remains restrained and dignified, literally any slander will be swallowed by the credulous and every foul scandal and shame can be confidently covered up.

But amid all their countless fiascoes and failures in every other field (including the highest per capita death rate from COVID-19 in Europe, and one of the highest in the world) the British remain world leaders at managing global Fake News. As long as the tone remains restrained and dignified, literally any slander will be swallowed by the credulous and every foul scandal and shame can be confidently covered up. The first important breakthrough in this fundamental reassessment of Orwell comes from one of the best books on him. “Finding George Orwell in Burma” was published in 2005 and written by “Emma Larkin”, a pseudonym for an outstanding American journalist in Asia whose identity I have long suspected to be an old friend and deeply respected colleague, and whose continued anonymity I respect.

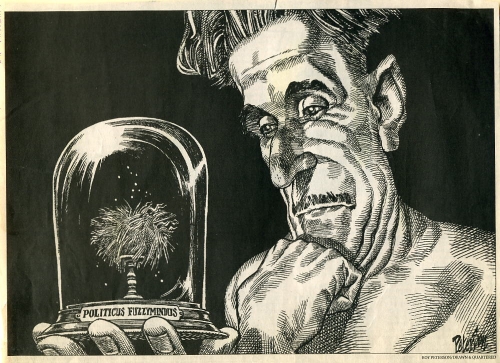

The first important breakthrough in this fundamental reassessment of Orwell comes from one of the best books on him. “Finding George Orwell in Burma” was published in 2005 and written by “Emma Larkin”, a pseudonym for an outstanding American journalist in Asia whose identity I have long suspected to be an old friend and deeply respected colleague, and whose continued anonymity I respect. The young Eric Blair was so disgusted by the experience that when he returned home he abandoned the respectable middle class life style he had always enjoyed and became, not just an idealistic socialist as many in those days did, but a penniless, starving tramp. He even abandoned his name and very identity. He suffered a radical personality collapse: He killed Eric Blair. He became George Orwell.

The young Eric Blair was so disgusted by the experience that when he returned home he abandoned the respectable middle class life style he had always enjoyed and became, not just an idealistic socialist as many in those days did, but a penniless, starving tramp. He even abandoned his name and very identity. He suffered a radical personality collapse: He killed Eric Blair. He became George Orwell.

Historien de formation, l’auteur plonge le lecteur à la fin de l’année 1941 dans une Angleterre vaincue et occupée par l’Allemagne. Si le roi George VI est prisonnier dans la Tour de Londres, son épouse et leurs filles, la princesse héritière Elizabeth et sa sœur Margaret, vivent en exil en Nouvelle-Zélande. Winston Churchill est pendu haut et court. À l’instar de l’éphémère « France libre » de Charles de Gaulle qui « s’est promu général et [qui] a déclaré qu’il était la voix de la France. Ça n’a jamais abouti à rien (p. 174) », la « Grande-Bretagne libre » s’incarne depuis l’Amérique du Nord dans un certain contre-amiral Conolly. Cette résistance extérieure complète une résistance intérieure plus ou moins balbutiante.

Historien de formation, l’auteur plonge le lecteur à la fin de l’année 1941 dans une Angleterre vaincue et occupée par l’Allemagne. Si le roi George VI est prisonnier dans la Tour de Londres, son épouse et leurs filles, la princesse héritière Elizabeth et sa sœur Margaret, vivent en exil en Nouvelle-Zélande. Winston Churchill est pendu haut et court. À l’instar de l’éphémère « France libre » de Charles de Gaulle qui « s’est promu général et [qui] a déclaré qu’il était la voix de la France. Ça n’a jamais abouti à rien (p. 174) », la « Grande-Bretagne libre » s’incarne depuis l’Amérique du Nord dans un certain contre-amiral Conolly. Cette résistance extérieure complète une résistance intérieure plus ou moins balbutiante.